Asia Report N°144

31 January 2008

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The violent crushing of protests led by Buddhist monks in Burma/Myanmar in late 2007 has caused even allies of the military government to recognise that change is desperately needed. China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) have thrown their support behind the efforts by the UN Secretary-General’s special envoy to re-open talks on national reconciliation, while the U.S. and others have stepped up their sanctions. But neither incomplete punitive measures nor intermittent talks are likely to bring about major reforms. Myanmar’s neighbours and the West must press together for a sustainable process of national reconciliation. This will require a long-term effort by all who can make a difference, combining robust diplomacy with serious efforts to address the deep-seated structural obstacles to peace, democracy and development.

The protests in August-September and, in particular, the government crackdown have shaken up the political status quo, the international community has been mobilised to an unprecedented extent, and there are indications that divergences of view have grown within the military. The death toll is uncertain but appears to have been substantially higher than the official figures, and the violence has profoundly disrupted religious life across the country. While extreme violence has been a daily occurrence in ethnic minority populated areas in the border regions, where governments have faced widespread armed rebellion for more than half a century, the recent events struck at the core of the state and have had serious reverberations within the Burman majority society, as well as the regime itself, which it will be difficult for the military leaders to ignore.

While these developments present important new opportunities for change, they must be viewed against the continuance of profound structural obstacles. The balance of power is still heavily weighted in favour of the army, whose top leaders continue to insist that only a strongly centralised, military-led state can hold the country together. There may be more hope that a new generation of military leaders can disown the failures of the past and seek new ways forward. But even if the political will for reform improves, Myanmar will still face immense challenges in overcoming the debilitating legacy of decades of conflict, poverty and institutional failure, which fuelled the recent crisis and could well overwhelm future governments as well.

The immediate challenges are to create a more durable negotiating process between government, opposition and ethnic groups and help alleviate the economic and humanitarian crisis that hampers reconciliation at all levels of society. At the same time, longer-term efforts are needed to encourage and support the emergence of a broader, more inclusive and better organised political society and to build the capacity of the state, civil society and individual households alike to deal with the many development challenges. To achieve these aims, all actors who have the ability to influence the situation need to become actively involved in working for change, and the comparative advantages each has must be mobilised to the fullest, with due respect for differences in national perspectives and interests.

RECOMMENDATIONS

To the International Community:

1. Agree to tightly structure engagement with Myanmar with three complementary elements extending beyond the Secretary-General’s current Group of Friends at the UN and allowing for a division of labour and different degrees of involvement with the military regime:

(a) the UN Secretary-General’s special adviser and envoy, Ibrahim Gambari, who provides a focal point for the overall coordination of international efforts and focuses on national reconciliation issues, including the nature and sequencing of political reforms and related human rights issues;

(b) cooperating closely with him, a small regional working group, composed of China and from ASEAN possibly Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam, which engages Myanmar directly in discussions on issues bearing on regional stability and development; and

(c) a support group, composed of influential Western governments, including Australia, Canada, the EU, France, Germany, Japan, Norway, the UK and the U.S., which keeps human rights at the top of the international agenda and structures inducements for change, including sanctions and incentives, as well as broader humanitarian and other aid programs.

To the UN Secretary-General:

2. Strengthen his good offices by:

(a) becoming directly involved in key negotiations with the Myanmar authorities, including through a personal visit to Naypyidaw in the near future;

(b) facilitating direct access to the Security Council, as well as to the Human Rights Council, for his special adviser and envoy, Gambari, when he needs it;

(c) encouraging his special adviser and envoy to focus on mediation between conflicting parties and viewpoints and leave primarily to the special rapporteur and other representatives of relevant UN human rights mechanisms the more public roles which may weaken his ability to build relations and confidence with all sides; and

(d) requesting sufficient resources from member states to support his good offices in the medium term, including for hiring necessary support staff and establishing an office in Myanmar or nearby.

To Regional Countries:

3. Provide unequivocal support for the good offices of the UN Secretary-General and his efforts, personally and through his special adviser and envoy, to move Myanmar towards national reconciliation and improvements in human rights.

4. Organise regional multiparty talks, including Myanmar, China and key ASEAN countries, to address issues of common concern, including by:

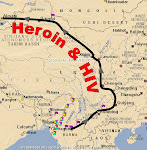

(a) establishing discussion on key peace and conflict issues, including the consolidation and broadening of existing ceasefire arrangements, combating transnational crime and integrating conflict-affected border areas into regional economies in a more sustainable manner;

(b) creating a forum in which to prioritise Myanmar’s development aims and how to link them with those of the region at large, possibly including a regional experts panel on development and a regional humanitarian mission;

(c) coordinating and strengthening regional support for the relevant law enforcement, development and capacity-building programs; and

(d) ensuring that state and private business practices serve the long-term interests of the region by contributing to peace and development in Myanmar.

To Western Countries (including Japan):

5. While allowing the UN and regional governments to take the diplomatic lead, work to establish an international environment conducive to their success, including by:

(a) maintaining focus on key human rights issues in all relevant forums, including the Security Council, and by supporting active engagement and access to Myanmar by the special rapporteur and other representatives of the relevant thematic human rights mechanisms;

(b) preparing and structuring a series of escalating targeted sanctions, focusing on:

i. restrictions on access by military, state and crony enterprises to international banking services;

ii. limiting access of selected generals and their immediate families to personal business opportunities, health care, shopping, and foreign education for their children; as well as

iii. a universal arms embargo; and

(c) offering incentives for reform in order to balance the threat and/or imposition of sanctions and give the military leadership positive motivation for change.

6. Organise a donors forum, which can work to:

(a) generate agreement on the nature and funding of an incentive package;

(b) strengthen the humanitarian response by:

i. scaling up existing effective programs in the health sector to ensure national impact;

ii. initiating new and broader programs to support basic education and income-generation;

iii. reaching internally displaced persons (IDPs) and others caught in the conflict zones, by combining programs from inside the country and across the border; and

iv. complementing aid delivery with policy dialogue and protection activities to ensure that harmful policies and practices are alleviated;

(c) strengthen the basis for future reforms and a successful transition to peace, democracy and a market economy by:

i. empowering disenfranchised groups;

ii. alleviating political, ethnic, religious and other divisions in communities, and building social capital;

iii. strengthening technical and administrative skills within state and local administrations, as well as civil society groups and private businesses;

iv. developing a peace economy in the conflict-affected border regions which can provide alternative livelihoods for former combatants; and

v. strengthening the coping mechanisms of individual households and communities; and

(d) start contingency planning for transitional and post-transitional programs to rebuild and reform key political and economic institutions, as well as social and physical infrastructure.

7. Invite the World Bank to initiate a comprehensive and sustained policy dialogue with the government and relevant political and civil society actors, including needs assessments and capacity-building efforts.

8. Undertake a comprehensive review of existing and proposed sanctions to assess their impact and revise their terms as necessary to ensure that the harm done to civilians is minimised, important complementary policies are not unreasonably restricted, and they can be lifted flexibly if there is appropriate progress.

Yangon/Jakarta/Brussels, 31 January 2008

တိတ်ဆိတ်သော သာယာမှု ရှိရာဆီ ခဏ...

-

Almost heaven, West Virginia

Blue Ridge Mountains, Shenandoah River

Life is old there, older than the trees

Younger than the mountains, growin' like a br...

3 months ago

No comments:

Post a Comment